Back to Basics: Knitting and Education

Teachers in my school district are in a bit of a funk this year. We’ve had four years of frozen salaries as well as pay cuts for individuals with master’s degrees or National Board Certification. We’ve lost five teacher work days (time we used in the past to plan, grade, and organize), and the new federal Race to the Top initiative (a program in which 48 states now participate) requires more professional development training and paperwork on our part. A new national curriculum (called the Common Core) also means that teachers must require all students to engage in reading complex texts and in using higher-order thinking skills to analyze and solve problems.

For most of my career I have taught honors and Advanced Placement levels and have attempted to challenge even the most gifted students. I’ve eschewed water-down, sanitized textbook excerpts of literature in favor of original works in their entirety. My students have always been required to read difficult novels, plays, poetry, and epics, archaic language and all. I have always understood that for some students, reading at the level such works require has been a daunting, if not an impossible task, because they lack the context of experience, vocabulary, and reading strategies to be successful. For these individuals, reading Spark’s Notes and listening to class discussions typically gives them enough superficial information to pass a test or write an essay on a piece of literature. After I lost the glistening idealism of a new teacher, I also relinquished my frustration with these struggling young people and came to understand their limitations a bit. I try to encourage them by sharing reading strategies and providing information about the social and historical context of a work of literature. I am always filled with hope that they will become competent readers of difficult texts—one day.

Early yesterday morning, as I lay in bed reading an article entitled “Beyond the Basics: Swatching the Lace Universe” by Deborah Newton in the spring issue of Interweave Knits, I was suddenly struck by a central problem of this whole Brave New World of education and how it relates to my own experiences learning to knit. Three years ago I would have looked at the pretty pictures that accompanied the article on lace and turned the page. I might have skimmed the text a little bit, but the words would have been intimidating and confusing. I was not ready to attack lace, either knitting it or reading about its complexities, until I had the muscle memory and rote experience of hours and hours (probably more like weeks and weeks) of simply knitting. My brain, in the past, could not process the structure of knitting, how knitting two stitches together makes the stitch lean one direction and slip, knit, pass over makes it lean the other. For nearly three years I have created all sorts of garments, some of them in quite complex patterns, but it was only about a month ago that I began to understand the “why” or garment construction, the notion of gauge, decreasing, increasing, etc., rather than just the “how.” For years, I’d just followed instructions, making little connection between the symbols on the page and how they related to the garment itself. Sometimes I’d find that I’d knitted ten rows and would look at my work only to find that there was a huge, glaring mistake eight rows down that I’d ignored because my connection had been with the written instructions or pattern, not the yarn itself.

|

| This article from Interweave Knits spring 2012 issue is very helpful in understanding exactly how lace "works" (or the whys of lace). |

|

| Click here for link to website. |

Many students are no more ready for the higher-order analytical thinking, the “why” that will be the focus of this new instruction than I was three years ago to knit a lacy mohair shawl. In fact, in testament to this idea, I can relate how I tried again and again a few years ago to attempt a simple faggot lace scarf in Knitting for Dummies and just couldn’t do it. Every row ended up being a different and incorrect number of stitches. Now I can knit lace, not like a champ—but I’m getting there. I simply needed practice, practice which builds confidence. I wasn’t ready to knit lace a few years ago, nor was I ready to understand the individual elements that go into garment construction—the whys of how a piece of knitwear is shaped and designed.

|

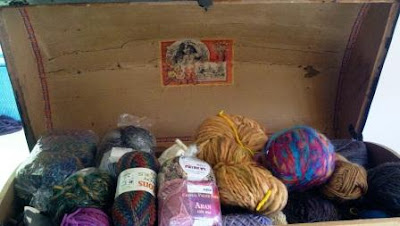

| Before I learned to knit, this trunk was filled with odds and ends. |

|

| Now, I am armed with hours of practice and this trunk is filled with an expanding stash. |

I can remember when my younger son was eight and was still struggling with his times tables. He had been given all the “whys” of multiplication at school, and was required to draw boxes illustrating the concept of multiplication every time he solved an equation. These boxes were nice, I suppose, but did nothing to mitigate his anger and tears when faced with multiplication problems. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that the very fact that he had not memorized his times tables affected his performance and confidence. It wouldn’t take a rocket scientist to come to my conclusion, but in our modern educational system, we give short shrift to inculcating basic skills, so I have students in my classroom who are asked to analyze the nuances of a text and to connect the themes of literature with life, but who have no clue what most of the words mean in a text and who cannot identify a verb in a sentence.

Like my son who struggled through a year of Kumon worksheets (Kumon is a tutoring program that emphasizes rote repetition to build knowledge and confidence), I required training and practice before I could dig deep into the theory part of knitting. Maybe I’m a slow learner, because not everyone requires this type of preparation. My sister-in-law became visually impaired a year ago and took up knitting soon after. She had worked for years and years as a computer engineer, so her mathematical and special abilities have to be superior to my own. I was talking with her the other day about knitting and she said, “I really have a problem with my eyes following the patterns, but I can calculate gauge and make up my own patterns really easily.” This statement is from the same woman who, with limited vision, was knitting socks a couple of weeks after she first learned to knit. Socks!

Anyway, my story and hers illustrate to me the mantra that I hear from teachers all the time. Students are different. A one-sized-fits-all curriculum is doomed for failure, unless we recognize that teachers, schools, and students are not failing if everyone doesn’t excel using the new standards. Not all knitters are ready to create an Alice Starmore Mary Tudor sweater or a vintage lace shawl, nor are all high school students able to read Moby Dick independently. Teachers are idealists at heart, though, and most of us believe that anything is possible . . . with time. The old adage, “Practice makes perfect,” makes sense. But in this world of teacher accountability, concentrated time building basic skills and motivation on the part of the student to practice those skills are elements of this equation for student success that aren’t addressed in the policy that’s handed down from Washington.

Practice is dismissed by dime-a-dozen educational Ph.D.’s as “Kill and drill,” but, ironically, students from around the globe who are inculcated in basic skills in a traditional manner seem to be exceeding students in the U.S. in academic achievement at higher levels. Maybe teachers, students, and parents would all be happier if we looked at education as we do knitting—parts of the process will be tedious, frustrating, and downright boring, but we have to work through these aspects (tearing out ten rows, for instance) in order to understand how to create something intricate and beautiful. The creation of this item and its subsequent rewards (both personal and professional) enrich our experience and build self-assurance that translates into success however we define this term.

Love it, Liz! Your words were eliquently written and really made me think about what we do, and why! Tonya

ReplyDelete